After nailing the Ninety-Five Theses to the church door in Wittenberg, the wayward Augustinian monk, Brother Martin gave a disputation in Heidelberg on April 26th 1518. Luther had been developing his ideas on indulgences, the role of the church, salvation, and the role of the theologian. Earlier that month, Brother Luther published a pamphlet called Eynn Sermon von dem Ablasz und Gnade or A Sermon on Indulgences and Grace. A powerful little piece written in a style of German that crossed regional dialects, it spread like wildfire throughout the Holy Roman Empire. Luther pointed out that indulgences do nothing to lead one to true repentance, but rather work against the grace God has given. Carefully avoiding the topic of contradicting the Pope directly, Luther insisted that the Pope simply was not reading the passages of scripture close enough. The Heidelberg Disputation then can be seen as a further articulation of these ideas and a thorough expansion of this pamphlet. Luther’s passionate disputation before the Augustinian order sent ripples through the church that eventually led to another disputation in Leipzig the following year.

A disputation is a defense of a thesis and in Heidelberg we see a precursor to Luther’s major writing period of the early 1520’s. Luther articulated in detail some of the key doctrines that would make his works the subject of study around Europe. Among these were the law of God and that of grace through faith, the mortality of all sin and the non-existence of venial sin, and the differences between the theologian of glory and the theologian of the cross.

Luther starts his disputation by focusing on the law of God. For this he relies on Romans which describes it as the law of sin and death. In 2 Corinthians 3:6 he quotes that the “written code kills.” Luther points out that this applies to “every law.” He states that though we are encouraged to do good, “nevertheless the opposite takes place, namely, that [we become] more wicked.” The problem for human beings in doing good works is that though we may try as we might to do them, we are impure in heart “for without grace and faith it is impossible to have a pure heart.” Our good works are not truly the product of our own hands but an “alien work of God.” Therefore, since we did not do them, but God did them through us by his grace, there is no such thing as human merit. This cut into the notion of indulgences, because they themselves relied on the efficacy of the merit of the saints.

An indulgence can be defined as “the remission of temporal punishment still due for a sin that has been sacramentally absolved.” They could be bought to help the person buying it or one of their loved ones. The indulgence system worked through a treasury of merit which the church had control of. Saints and apostles did plenty of “good works” on earth such that their treasury in heaven was massive. Therefore, for a small payment, the church could transfer the merit from the saints large account to the purchaser of the indulgence’s over-drafted account so as to bring them out of their sin and into an enhanced state of grace and shorten or eliminate their time in purgatory. Luther challenged the idea of merit in good works and did so by challenging the idea that it could be possible to have a good work.

Luther starts by debunking the notion of venial sin. Venial sin is defined as “an offense that is judged to be minor or committed without deliberate intent and thus does not estrange the soul from the grace of God.” A mortal sin on the other hand is defined as “a sin…that is so heinous it deprives the soul of sanctifying grace and causes damnation if unpardoned at the time of death.” What Luther is doing is echoing Isaiah who says “all our righteous acts are like filthy rags.” It is not so much the actions themselves, as the one doing it. Luther uses this comparison, “If someone cuts with a rusty and rough hatchet, even though the worker is a good craftsman, the hatchet leaves bad, jagged, and ugly gashes. So it is when God works through us.” Though we aim to do good works, we are stained by a world mired in sin and as such, our works are flawed, yet we seek to glory in them. We want to bring credit to ourselves and think that somehow we did that good work by our own strength. In fact, Luther accuses those who believe their works are meritorious as robbers of God’s glory.

Luther says, “To trust in works, which one ought to do in fear, is equivalent to giving oneself the honor and taking it from God, to whom fear is due in connection with every work. But this is completely wrong, namely to please oneself, to enjoy oneself in one’s works, and to adore oneself as an idol.” The truly righteous see good works not as the source of their confidence. The truly righteous seek to do works to please God himself who is their confidence.

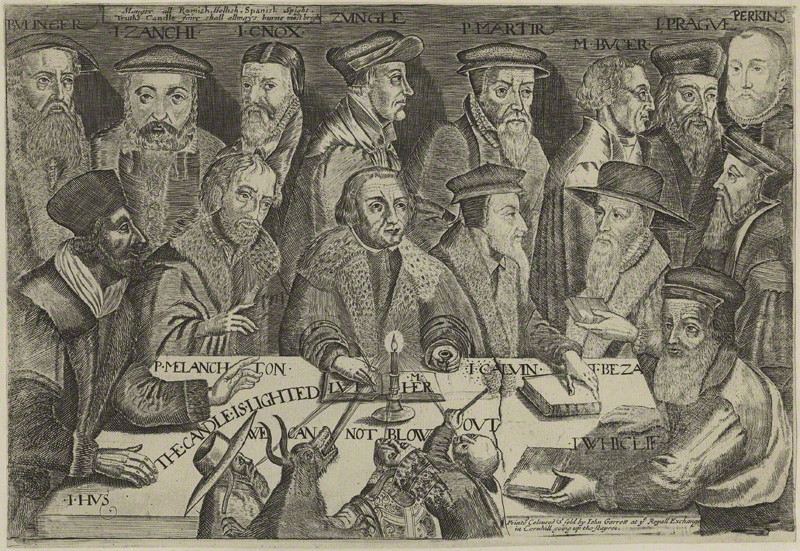

Gemaelde von G. Baumann: “Brenz und Isenmann bei Luther in Heidelberg, 1854”

This confidence in works and pride, Luther believes, is the reason for so much strife. They do not see all of their sin as mortal sin. Luther asserts, “God is constantly deprived of the glory which is due to him and which is transferred to other things…” Most often, it is transferred to man. In addition, these works are dead because they are not done in Christ, but for one’s pride. Because the “will is captive and subject to sin….it is not free except to do evil.” In accordance with Augustine, Luther urges that “free will without grace has the power to do nothing but sin.” As a result, the very concept of venial sins is completely done away with. In other words, all sin is mortal sin.

Luther then uses mortal sins to make a point about despair. He says there is no reason to remain in despair. In fact, Luther calls people to “fall down and pray for grace and place your hope in Christ in whom is your salvation, life and resurrection. For this reason the law makes us aware of sin so that, having recognized our sin, we may seek and receive grace.” Grace Luther says exalts and brings hope and mercy. On the other hand, Law humbles, imparts fear and wrath and a knowledge of sin that with humility ought to bring us to an understanding of God’s grace. This is the problem with those who trust in their good works: they are not humble. Those who are puffed up in their works “cannot be humble who do not recognize that they are damnable whose sin smells to high heaven.”

Here we hit a remarkable chord where Luther intersects the contemporary Protestant church. There is an idea out there that “I’m basically a good person.” Are you? If so, are you “prepared to receive the grace of Christ”? Luther points out that, “he who acts simply in accordance with his ability and believes that he is thereby doing something good does not seem worthless to himself, nor does he despair of his own strength. Indeed, he is so presumptuous that he strives for grace in reliance on his own strength.” This is the problem with those who feel they are basically good people. They are unable to truly despair of their sin and recognize their need of Christ. Which in itself brings us to Luther’s final point on the theologians of glory and the theologians of the cross.

Theologians of glory emphasize virtue, wisdom, justice and goodness. These are the invisible things of God and they worship; pillars of ideology and theology. On the other hand, the theologian of the cross emphasizes and recognizes the visible crucified Christ. He is motivated not by virtue, but by the suffering of Christ on the cross. The theologian of glory calls evil good and good evil in the cross, but the theologian of the cross “calls the thing what it actually is.” The theologian of glory prefers works, glory, strength, and wisdom. Meanwhile, the theologian of the cross prefers the cross, suffering, weakness, and folly. Theologians of glory see their good works as adding to their own glory and making them better in the sight of God. A theologian of the cross does not boast in his works, but says all of them are “filthy rags.” Such a person neither boasts or “is disturbed if God should choose or not choose to do a work in him.”

Luther, hammering on the theologians of glory, argues that “it is impossible for a person not to be puffed up by his ‘good works’ unless he has first been deflated and destroyed by suffering and evil until he knows that he is worthless and that his works are not his but God’s. That wisdom which sees the invisible things of God in works as perceived by man is completely puffed up, blinded, and hardened.” This is because those who put their trust in wisdom will never have enough wisdom. Quoting Ecclesiastes, Luther predicates his comment “the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing.” Whether power or praise or wisdom, all of these things are not Christ himself. Therefore, Luther claims rather philosophically, that “the remedy for curing desire does not lie in satisfying it, but in extinguishing it; …he who wishes to become wise does not seek wisdom by progressing toward it, but becomes a fool by retrogressing into seeking folly…[he] must flee rather than seek power…. This is the wisdom which is folly to the world.” Countering the one who seeks glory for themselves, all glory must be given to Christ.

Kicking off Reformation month 2016, I attempted to explain Luther’s commentary on the Galatians and how the world bears the Gospel a grudge. This is why. The gospel calls us to put our faith in the suffering of Christ on the cross. It urges us to flee fame, power, fortune, wisdom, and grandeur for ourselves. It demands humility and it holds no place for the glory of man, but gives all the glory to God himself. “The law says ‘do this’ and it is never done. Grace says, ‘believe in this,’ and everything is already done. The is to let Christ dwell within us and to act through us. Good is not something that we do but is something that is conferred “upon the bad and needy person.” As pertaining to justification and salvation, this concept can be seen as leading away from a concept of infusion of grace and toward a concept of imputation of grace; a challenging step and stumbling block for the Roman church.

As one can imagine for the time period, the ideas expressed in the Heidelberg Disputation took Rome to task in several ways. It threw out the scaffolding which held up the system of merits on which indulgences where sold. It disempowered the church’s leaders to forgive sin, but placed it squarely upon the grace of God to forgive sin based on the merit of Christ. This revival of Augustinian thought and the doctrines of grace put large fissures in the façade that the Roman church had created. It set the stage for further developments and helped open the door wide toward reformation. Today’s church would do well to remember it.

All Martin Luther quotes are from the text of the Heidelberg Disputation

“Heidelberg Disputation.” 26 April 1518. The Book of Concord: The Confessions of the Lutheran Church. Accessed 5 October 2016. http://bookofconcord.org/heidelberg.php

All Definitions are from the American Heritage Dictionary

“indulgence.” The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. 4th Edition. (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009) 895.

“mortal sin.” The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. 4th Edition. (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009) 1145.

“venial sin.” The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. 4th Edition. (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009) 1908.